Hubbert peak theory

The Hubbert peak theory posits that for any given geographical area, from an individual oil-producing region to the planet as a whole, the rate of petroleum production tends to follow a bell-shaped curve. It is one of the primary theories on peak oil.

Choosing a particular curve determines a point of maximum production based on discovery rates, production rates and cumulative production. Early in the curve (pre-peak), the production rate increases because of the discovery rate and the addition of infrastructure. Late in the curve (post-peak), production declines because of resource depletion.

The Hubbert peak theory is based on the observation that the amount of oil under the ground in any region is finite, therefore the rate of discovery which initially increases quickly must reach a maximum and decline. In the US, oil extraction followed the discovery curve after a time lag of 32 to 35 years.[1][2] The theory is named after American geophysicist M. King Hubbert, who created a method of modeling the production curve given an assumed ultimate recovery volume.

Contents |

Hubbert's peak

"Hubbert's peak" can refer to the peaking of production of a particular area, which has now been observed for many fields and regions.

Hubbert's Peak was achieved in the continental US in the early 1970s. Oil production peaked at 10,200,000 barrels per day (1,620,000 m3/d). Since then, it has been in a gradual decline.

Peak oil as a proper noun, or "Hubbert's peak" applied more generally, refers to a singular event in history: the peak of the entire planet's oil production. After Peak Oil, according to the Hubbert Peak Theory, the rate of oil production on Earth would enter a terminal decline. On the basis of his theory, in a paper[3] he presented to the American Petroleum Institute in 1956, Hubbert correctly predicted that production of oil from conventional sources would peak in the continental United States around 1965-1970. Hubbert further predicted a worldwide peak at "about half a century" from publication and approximately 12 gigabarrels (GB) a year in magnitude. In a 1976 TV interview[4] Hubbert added that the actions of OPEC might flatten the global production curve but this would only delay the peak for perhaps 10 years.

Hubbert's theory

Hubbert curve

In 1956, Hubbert proposed that fossil fuel production in a given region over time would follow a roughly bell-shaped curve without giving a precise formula; he later used the Hubbert curve, the derivative of the logistic curve,[5] for estimating future production using past observed discoveries.

Hubbert assumed that after fossil fuel reserves (oil reserves, coal reserves, and natural gas reserves) are discovered, production at first increases approximately exponentially, as more extraction commences and more efficient facilities are installed. At some point, a peak output is reached, and production begins declining until it approximates an exponential decline.

The Hubbert curve satisfies these constraints. Furthermore, it is roughly symmetrical, with the peak of production reached when about half of the fossil fuel that will ultimately be produced has been produced. It also has a single peak.

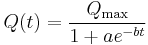

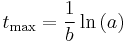

Given past oil discovery and production data, a Hubbert curve that attempts to approximate past discovery data may be constructed and used to provide estimates for future production. In particular, the date of peak oil production or the total amount of oil ultimately produced can be estimated that way. Cavallo[6] defines the Hubbert curve used to predict the U.S. peak as the derivative of:

where  max is the total resource available (ultimate recovery of crude oil),

max is the total resource available (ultimate recovery of crude oil),  the cumulative production, and

the cumulative production, and  and

and  are constants. The year of maximum annual production (peak) is:

are constants. The year of maximum annual production (peak) is:

Use of multiple curves

The sum of multiple Hubbert curves, a technique not developed by Hubbert himself, may be used in order to model more complicated real life scenarios.[7]

Definition of reserves

Almost all of Hubbert peaks must be put in the context of high ore grade. Except for fissionable materials, any resource, including oil, is theoretically recoverable from the environment with the right technology. In contrast, Hubbert was concerned with "easy" oil, "easy" metals, and so forth that could be recovered without greatly advanced mining efforts and how to time the necessity of such resource acquisition advancements or substitutions by knowing an "easy" resource's probable peak. Also, as reserves become more difficult to extract there is the possibility that mining or alternatives are too expensive for developing countries.

For heavy crude or deep water drilling attempts, such as Noxal oil field or tar sands or oil shale, the price of the oil extracted will have to include the extra effort required to mine these resources. According to the U.S. Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, Regulation and Enforcement(formerly, the Minerals Management Service), areas such as the Outer Continental Shelf may also incur higher costs due to environmental concerns. So not all oil reserves are equal, and the more difficult reserves are predicted by Hubbert as being typical of the post-peak side of the Hubbert curve.

Reliability

Hubbert, in his 1956 paper,[3] presented two scenarios for US conventional oil production (crude oil + condensate):

- most likely estimate: a logistic curve with a logistic growth rate equal to 6%, an ultimate resource equal to 150 Giga-barrels (Gb) and a peak in 1965.

- upper-bound estimate: a logistic curve with a logistic growth rate equal to 6% and ultimate resource equal to 200 Giga-barrels and a peak in 1970.

Hubbert's upper-bound estimate, which he regarded as optimistic, accurately predicted that US oil production would peak in 1970. Forty years later, the upper-bound estimate has also proven to be very accurate in terms of cumulative production, less so in terms of annual production. For 2005, the upper-bound Hubbert model predicts 178.2 Gb cumulative and 1.17 Gb current production; actual US production was 176.4 Gb cumulative crude oil + condensate (1% lower than the upper bound estimate), with annual production of 1.55 Gb (32% higher than the upper bound estimate).

A post-hoc analysis of peaked oil wells, fields, regions and nations found that Hubbert's model was the "most widely useful"(providing the best fit to the data), though many areas studied had a sharper "peak" than predicted.[8]

Economics

Energy return on energy investment

When oil production first began in the mid-nineteenth century, the largest oil fields recovered fifty barrels of oil for every barrel used in the extraction, transportation and refining. This ratio is often referred to as the Energy Return on Energy Investment (EROI or EROEI). Currently, between one and five barrels of oil are recovered for each barrel-equivalent of energy used in the recovery process. As the EROEI drops to one, or equivalently the Net energy gain falls to zero, the oil production is no longer a net energy source. This happens long before the resource is physically exhausted.

Note that it is important to understand the distinction between a barrel of oil, which is a measure of oil, and a barrel of oil equivalent (BOE), which is a measure of energy. Many sources of energy, such as fission, solar, wind, and coal, are not subject to the same near-term supply restrictions that oil is. Accordingly, even an oil source with an EROEI of 0.5 can be usefully exploited if the energy required to produce that oil comes from a cheap and plentiful energy source. Availability of cheap, but hard to transport, natural gas in some oil fields has led to using natural gas to fuel enhanced oil recovery. Similarly, natural gas in huge amounts is used to power most Athabasca Tar Sands plants. Cheap natural gas has also led to Ethanol fuel produced with a net EROEI of less than 1, although figures in this area are controversial because methods to measure EROEI are in debate.

Growth-based economic models

Insofar as economic growth is driven by oil consumption growth, post-peak societies must adapt. Hubbert believed:[9]

| “ | Our principal constraints are cultural. During the last two centuries we have known nothing but exponential growth and in parallel we have evolved what amounts to an exponential-growth culture, a culture so heavily dependent upon the continuance of exponential growth for its stability that it is incapable of reckoning with problems of nongrowth. | ” |

Some economists describe the problem as uneconomic growth or a false economy. At the political right, Fred Ikle has warned about "conservatives addicted to the Utopia of Perpetual Growth".[10] Brief oil interruptions in 1973 and 1979 markedly slowed - but did not stop - the growth of world GDP.[11]

Between 1950 and 1984, as the Green Revolution transformed agriculture around the globe, world grain production increased by 250%. The energy for the Green Revolution was provided by fossil fuels in the form of fertilizers (natural gas), pesticides (oil), and hydrocarbon fueled irrigation.[12]

David Pimentel, professor of ecology and agriculture at Cornell University, and Mario Giampietro, senior researcher at the National Research Institute on Food and Nutrition (INRAN), place in their study Food, Land, Population and the U.S. Economy the maximum U.S. population for a sustainable economy at 200 million. To achieve a sustainable economy world population will have to be reduced by two-thirds, says the study.[13] Without population reduction, this study predicts an agricultural crisis beginning in 2020, becoming critical c. 2050. The peaking of global oil along with the decline in regional natural gas production may precipitate this agricultural crisis sooner than generally expected. Dale Allen Pfeiffer claims that coming decades could see spiraling food prices without relief and massive starvation on a global level such as never experienced before.[14][15]

Hubbert peaks

Although Hubbert peak theory receives most attention in relation to peak oil production, it has also been applied to other natural resources.

Natural gas

Doug Reynolds predicted in 2005 that the North American peak would occur in 2007.[16] Bentley (p. 189) predicted a world "decline in conventional gas production from about 2020".[17]

Coal

Although observers believe that peak coal is significantly further out than peak oil, Hubbert studied the specific example of anthracite in the USA, a high grade coal, whose production peaked in the 1920s. Hubbert found that Anthracite matches a curve closely.[18] Pennsylvania's coal production also matches Hubbert's curve closely, but this does not mean that coal in Pennsylvania is exhausted—far from it. If production in Pennsylvania returned at its all time high, there are reserves for 190 years. Hubbert had recoverable coal reserves worldwide at 2500 × 109 metric tons and peaking around 2150 (depending on usage).

More recent estimates suggest an earlier peak. Coal: Resources and Future Production (PDF 630KB[19]), published on April 5, 2007 by the Energy Watch Group (EWG), which reports to the German Parliament, found that global coal production could peak in as few as 15 years.[20] Reporting on this Richard Heinberg also notes that the date of peak annual energetic extraction from coal will likely come earlier than the date of peak in quantity of coal (tons per year) extracted as the most energy-dense types of coal have been mined most extensively.[21] A second study, The Future of Coal by B. Kavalov and S. D. Peteves of the Institute for Energy (IFE), prepared for European Commission Joint Research Centre, reaches similar conclusions and states that ""coal might not be so abundant, widely available and reliable as an energy source in the future".[20]

Work by David Rutledge of Caltech predicts that the total of world coal production will amount to only about 450 gigatonnes.[22] This implies that coal is running out faster than usually assumed.

Finally, insofar as global peak oil and peak in natural gas are expected anywhere from imminently to within decades at most, any increase in coal production (mining) per annum to compensate for declines in oil or natural gas production, would necessarily translate to an earlier date of peak as compared with peak coal under a scenario in which annual production remains constant.

Fissionable materials

In a paper in 1956,[23] after a review of US fissionable reserves, Hubbert notes of nuclear power:

| “ | There is promise, however, provided mankind can solve its international problems and not destroy itself with nuclear weapons, and provided world population (which is now expanding at such a rate as to double in less than a century) can somehow be brought under control, that we may at last have found an energy supply adequate for our needs for at least the next few centuries of the "foreseeable future." | ” |

Technologies such as the thorium fuel cycle, reprocessing and fast breeders can, in theory, considerably extend the life of uranium reserves. Roscoe Bartlett claims[24]

| “ | Our current throwaway nuclear cycle uses up the world reserve of low-cost uranium in about 20 years. | ” |

Caltech physics professor David Goodstein has stated[25] that

| “ | ... you would have to build 10,000 of the largest power plants that are feasible by engineering standards in order to replace the 10 terawatts of fossil fuel we're burning today ... that's a staggering amount and if you did that, the known reserves of uranium would last for 10 to 20 years at that burn rate. So, it's at best a bridging technology ... You can use the rest of the uranium to breed plutonium 239 then we'd have at least 100 times as much fuel to use. But that means you're making plutonium, which is an extremely dangerous thing to do in the dangerous world that we live in. | ” |

Helium

Almost all helium on Earth is a result of radioactive decay of uranium and thorium. Helium is extracted by fractional distillation from natural gas, which contains up to 7% helium. The world's largest helium-rich natural gas fields are found in the United States, especially in the Hugoton and nearby gas fields in Kansas, Oklahoma, and Texas. The extracted helium is stored underground in the National Helium Reserve near Amarillo, Texas, the self-proclaimed "Helium Capital of the World". Helium production is expected to decline along with natural gas production in these areas.

Helium is the second-lightest chemical element in the Universe, causing it to rise to the upper layers of Earth's atmosphere. Helium atoms are so light that the Earth's gravity field is simply not strong enough to trap helium in the atmosphere and it dissipates slowly into space and is lost forever.[26]

Transition metals

Hubbert applied his theory to "rock containing an abnormally high concentration of a given metal"[27] and reasoned that the peak production for metals such as copper, tin, lead, zinc and others would occur in the time frame of decades and iron in the time frame of two centuries like coal. The price of copper rose 500% between 2003 and 2007[28] and was attributed by some to peak copper.[29][30] Copper prices later fell, along with many other commodities and stock prices, as demand shrank from fear of a global recession.[31] Lithium availability is a concern for a fleet of Li-ion battery using cars but a paper published in 1996 estimated that world reserves are adequate for at least 50 years.[32] A similar prediction[33] for platinum use in fuel cells notes that the metal could be easily recycled.

Precious metals

The possibility of Peak Gold has emerged recently [5]. Aaron Regent president of the Canadian gold giant Barrik Gold said that global output has been falling by roughly one million ounces a year since the start of the decade. The total global mine supply has dropped by 10pc as ore quality erodes, implying that the roaring bull market of the last eight years may have further to run. "There is a strong case to be made that we are already at 'peak gold'," he told The Daily Telegraph at the RBC's annual gold conference in London. "Production peaked around 2000 and it has been in decline ever since, and we forecast that decline to continue. It is increasingly difficult to find ore," he said.

Ore grades have fallen from around 12 grams per tonne in 1950 to nearer 3 grams in the US, Canada, and Australia. South Africa's output has halved since peaking in 1970. Output fell a further 14 percent in South Africa in 2008 as companies were forced to dig ever deeper - at greater cost - to replace depleted reserves.

Phosphorus

Phosphorus supplies are essential to farming and depletion of reserves is estimated at somewhere from 60 to 130 years.[34] According to a 2008 study, the total reserves of phosphorus are estimated to be approximately 3,200 MT, with a peak production at 28 MT/year in 2034.[35] Individual country's supplies vary widely; without a recycling initiative America's supply[36] is estimated around 30 years.[37] Phosphorus supplies affect agricultural output which in turn limits alternative fuels such as biodiesel and ethanol. Its increasing price and scarcity (global price of rock phosphate rose 8-fold in the 2 years to mid 2008) could change global agricultural patterns. Lands, perceived as marginal because of remoteness, but with very high phosphorus content, such as the Gran Chaco[38] may get more agricultural development, while other farming areas, where nutrients are a constraint, may drop below the line of profitability.

Peak water

Hubbert's original analysis did not apply to renewable resources. However, over-exploitation often results in a Hubbert peak nonetheless. A modified Hubbert curve applies to any resource that can be harvested faster than it can be replaced.[39]

For example, a reserve such as the Ogallala Aquifer can be mined at a rate that far exceeds replenishment. This turns much of the world's underground water[40] and lakes[41] into finite resources with peak usage debates similar to oil. These debates usually center around agriculture and suburban water usage but generation of electricity[42] from nuclear energy or coal and tar sands mining mentioned above is also water resource intensive. The term fossil water is sometimes used to describe aquifers whose water is not being recharged.

Renewable resources

- Fisheries: At least one researcher has attempted to perform Hubbert linearization (Hubbert curve) on the whaling industry, as well as charting the transparently dependent price of caviar on sturgeon depletion.[43] Another example is the cod of the North Sea.[44] The comparison of the cases of fisheries and of mineral extraction tells us that the human pressure on the environment is causing a wide range of resources to go through a depletion cycle which follows a Hubbert curve.

Criticisms

Economist Michael Lynch[45] argues that the theory behind the Hubbert curve is too simplistic and relies on an overly Malthusian point of view.[46] Lynch claims that Campbell's predictions for world oil production are strongly biased towards underestimates, and that Campbell has repeatedly pushed back the date.[47][48]

Leonardo Maugeri, vice president of the Italian energy company Eni, argues that nearly all of peak estimates do not take into account unconventional oil even though the availability of these resources is significant and the costs of extraction and processing, while still very high, are falling because of improved technology. He also notes that the recovery rate from existing world oil fields has increased from about 22% in 1980 to 35% today because of new technology and predicts this trend will continue. The ratio between proven oil reserves and current production has constantly improved, passing from 20 years in 1948 to 35 years in 1972 and reaching about 40 years in 2003.[49] These improvements occurred even with low investment in new exploration and upgrading technology because of the low oil prices during the last 20 years. However, Maugeri feels that encouraging more exploration will require relatively high oil prices.[50]

Edward Luttwak, an economist and historian, claims that unrest in countries such as Russia, Iran and Iraq has led to a massive underestimate of oil reserves.[51] The Association for the Study of Peak Oil and Gas, or ASPO responds by claiming neither Russia nor Iran are troubled by unrest currently, but Iraq is.[52]

Cambridge Energy Research Associates authored a report that is critical of Hubbert-influenced predictions:[53]

| “ | Despite his valuable contribution, M. King Hubbert's methodology falls down because it does not consider likely resource growth, application of new technology, basic commercial factors, or the impact of geopolitics on production. His approach does not work in all cases-including on the United States itself-and cannot reliably model a global production outlook. Put more simply, the case for the imminent peak is flawed. As it is, production in 2005 in the Lower 48 in the United States was 66 percent higher than Hubbert projected. | ” |

CERA does not believe there will be an endless abundance of oil, but instead believes that global production will eventually follow an “undulating plateau” for one or more decades before declining slowly,[54] and that production will reach 40 Mb/d by 2015.[55]

Alfred J. Cavallo, while predicting a conventional oil supply shortage by no later than 2015, does not think Hubbert's peak is the correct theory to apply to world production.[56]

See also

Notes

- ^ Jean Laherrere, "Forecasting production from discovery", ASPO Lisbon May 19–20, 2005 [1]

- ^ J.R. Wood, Michigan Technical University Geology Department Oil Seminar 2003 [2]

- ^ a b Nuclear Energy and the Fossil Fuels,M.K. Hubbert, Presented before the Spring Meeting of the Southern District, American Petroleum Institute, Plaza Hotel, San Antonio, Texas, March 7–8-9, 1956 [3]

- ^ YouTube - 1976 Hubbert Clip

- ^ Bartlett A.A 1999 ,"An Analysis of U.S. and World Oil Production Patterns Using Hubbert-Style Curves." Mathematical Geology.

- ^ Hubbert’s Petroleum Production Model: An Evaluation and Implications for World Oil Production Forecasts, Alfred J. Cavallo, Natural Resources Research,Vol. 13,No. 4, December 2004 [4]

- ^ Laherrère, J.H. (Feb 18 2000). "The Hubbert curve : its strengths and weaknesses". http://dieoff.org. http://dieoff.org/page191.htm. Retrieved September 16 2011.

- ^ Brandt, A. R. (2007). "Testing Hubbert". Energy Policy 35 (5): 3074–3088. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2006.11.004. http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0301421506004265.

- ^ http://www.hubbertpeak.com/hubbert/wwf1976/

- ^ http://dieoff.org/page68.htm

- ^ http://www.imf.org/external/np/speeches/2006/pdf/050206.pdf

- ^ How peak oil could lead to starvation

- ^ Eating Fossil Fuels | EnergyBulletin.net

- ^ Peak Oil: the threat to our food security

- ^ Agriculture Meets Peak Oil

- ^ White, Bill (December 17, 2005). "State's consultant says nation is primed for using Alaska gas". Anchorage Daily News. http://dwb.adn.com/money/industries/oil/v-printer/story/7296501p-7208184c.html.

- ^ Bentley, R.W. (2002). "Viewpoint - Global oil & gas depletion: an overview" (PDF). Energy Policy 30 (3): 189–205. doi:10.1016/S0301-4215(01)00144-6. http://www.oilcrisis.com/bentley/depletionOverview.pdf.

- ^ GEO 3005: Earth Resources

- ^ http://www.energywatchgroup.org/files/Coalreport.pdf

- ^ a b http://www.energybulletin.net/29919.html

- ^ http://www.richardheinberg.com/museletter/179

- ^ "Coal: Bleak outlook for the black stuff", by David Strahan, New Scientist, January 19, 2008, pp. 38-41.

- ^ http://www.hubbertpeak.com/hubbert/1956/1956.pdf

- ^ http://www.bartlett.house.gov/uploadedfiles/5-2-06%20Oil%20Speech.pdf

- ^ http://www.energybulletin.net/3322.html

- ^ Kockarts, G. (1973). "Helium in the Terrestrial Atmosphere". Space Science Reviews (Space Science Reviews) 14 (6, pp.723–757): 723. Bibcode 1973SSRv...14..723K. doi:10.1007/BF00224775.

- ^ http://www.hubbertpeak.com/hubbert/wwf1976

- ^ http://minerals.usgs.gov/minerals/pubs/commodity/copper/mcs-2008-coppe.pdf Copper Statistics and Information, 2007]. USGS

- ^ Andrew Leonard (2006-03-02). "Peak copper?". Salon - How the World Works. http://www.salon.com/tech/htww/2006/03/02/peak_copper/index.html. Retrieved 2008-03-23.

- ^ http://news.silverseek.com/CharlestonVoice/1135873932.php

- ^ COMMODITIES-Demand fears hit oil, metals prices, January 29, 2009.

- ^ http://cat.inist.fr/?aModele=afficheN&cpsidt=2530187

- ^ http://www.dft.gov.uk/stellent/groups/dft_roads/documents/page/dft_roads_024056-01.hcsp

- ^ http://www.apda.pt/apda_resources/APDA.Biblioteca/eureau%5Cposition%20papers%5Cthe%20reuse%20of%20phosphorus.pdf

- ^ Stuart White, Dana Cordell (2008). "Peak Phosphorus: the sequel to Peak Oil". Global Phosphorus Research Initiative (GPRI). http://phosphorusfutures.net/peak-phosphorus. Retrieved 2009-12-11.

- ^ http://minerals.usgs.gov/minerals/pubs/commodity/phosphate_rock/phospmcs06.pdf

- ^ http://www.ecosanres.org/PDF%20files/Fact_sheets/ESR4lowres.pdf

- ^ Don Nicol. "A postcard from the central Chaco". http://www.breedleader.com.au/images/chaco%20postcard%20.pdf. Retrieved 2009-01-23. "alluvial sandy soils have phosphorus levels of up to 200-300 ppm"

- ^ Meena Palaniappan and Peter H. Gleick (2008). "The World's Water 2008-2009, Ch 1.". Pacific Institute. http://www.worldwater.org/data20082009/ch01.pdf. Retrieved 2009-01-31.

- ^ http://www.uswaternews.com/archives/arcsupply/6worllarg2.html

- ^ http://www.earth-policy.org/Updates/2005/Update47_data.htm

- ^ http://www.epa.gov/cleanrgy/water_resource.htm

- ^ http://www.aspoitalia.net/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=34&Itemid=39

- ^ http://www.hubbertpeak.com/laherrere/multihub.htm

- ^ http://www.energyseer.com/MikeLynch.html

- ^ http://www.energyseer.com/NewPessimism.pdf

- ^ http://www.hubbertpeak.com/Lynch/

- ^ Campbell, CJ (2005). Oil Crisis. Brentwood, Essex, England: Multi-Science Pub. Co.. pp. 90. ISBN 0906522390.

- ^ Maugeri, L. (2004). "Oil: Never Cry Wolf—Why the Petroleum Age Is Far from over". Science 304 (5674): 1114–5. doi:10.1126/science.1096427. PMID 15155935. http://www.condition.org/sm4602.htm.

- ^ "Oil, Oil Everywhere". Forbes. July 24, 2006. http://www.forbes.com/home/free_forbes/2006/0724/042.html.

- ^ "The truth about global oil supply". http://www.thefirstpost.co.uk/index.php?menuID=1&subID=18.

- ^ http://www.peakoil.net/Luttwak.html

- ^ http://cera.ecnext.com/coms2/summary_0236-821_ITM

- ^ CERA says peak oil theory is faulty Energy Bulletin November 14, 2006

- ^ http://www.energybulletin.net/node/19120

- ^ http://www.energybulletin.net/6271.html

References

- "Feature on United States oil production." (November, 2002) ASPO Newsletter #23.

- Greene, D.L. & J.L. Hopson. (2003). Running Out of and Into Oil: Analyzing Global Depletion and Transition Through 2050 ORNL/TM-2003/259, Oak Ridge National Laboratory, Oak Ridge, Tennessee, October

- Economists Challenge Causal Link Between Oil Shocks And Recessions (August 30, 2004). Middle East Economic Survey VOL. XLVII No 35

- Hubbert, M.K. (1982). Techniques of Prediction as Applied to Production of Oil and Gas, US Department of Commerce, NBS Special Publication 631, May 1982

External links

Sites

- U.S. Energy Information Agency Petroleum Data

- Association for the Study of Peak Oil

- PeakOil.com

- Oil Depletion Analysis Centre in the United Kingdom

- PowerSwitch in the United Kingdom

- Energy Bulletin Peak Oil related articles

- The Oil Drum Discussions about Energy and our Future

- Carbon War

- Global Oil Watch - Extensive peak oil library

- Energy Export Databrowser-Visual review of production and consumption trends for individual nations; data from the British Petroleum Statistical Review

Documentaries

- The Oilcrash, 2006

Online videos

Articles

- M. King Hubbert on the Nature of Growth. 1974

- El mundo ante el cenit del petróleo Fernando Bullón Miró

- M. King Hubbert, "Energy from Fossil Fuels", Science, vol. 109, pp. 103–109, February 4, 1949

- Technocracy, Hubbert and peak oil Article from The North American Technocrat

- David Hughes on Canadian Oil and Gas Transcribed interview of a Geologist with the Geological Survey of Canada. 30 December 2006.

- Aviation & Peak Oil Airways Magazine article by Analyst / Economist (July 2006)

Reports, essays and lectures

- Doctoral thesis about Peak Oil

- Review: Oil-based technology and economy - prospects for the future The Danish Board of Technology (Teknologirådet)

- Peakoil conference 19-20 October 2004

- Graph showing oil production in lower 48 US states following Hubbert's predictions

- Trends in Oil Supply and Demand, Potential for Peaking of Conventional Oil Production, and Possible Mitigation Options: A Summary Report of the Workshop (2006), National Research Council

- The End of Oil, essay 1.pdf, Very concise peak-oil study by Bob Lloyd, July 2005

- Peak Oil Theory – “World Running Out of Oil Soon” – Is Faulty; Could Distort Policy & Energy Debate

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||